County schools going virtual

Published 3:17 pm Monday, January 24, 2011

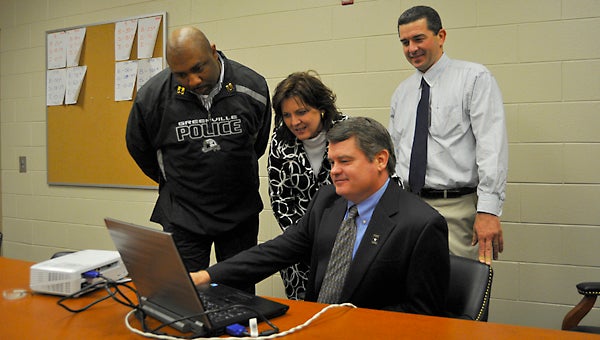

Left to right, Capt. Anthony Barganier of the Greenville police, W.O. Parmer principal Catherine Sawicki, AUM Consultant Lamar Davis, and Greenville Middle School assistant principal Kent McNaughton observe some of the functions of Virtual Alabama on Davis' computer. (Advocate Staff, Kevin Pearcey)

School was thought to be a safe place once. Sure, bullies patrolled the playgrounds looking for lunch money. There was the inevitable fist thrown in the classroom over some petty argument. Teenagers hurt each others feelings with words (and still do).

Detention once solved everything. That, and the paddle, from both principals and parents. No one thought of bringing a gun to school and, if they did, it was in a hunting rack in their pick-up truck’s window where it stayed.

But in today’s perilous world, where school shootings (and public massacres in general) frequently break on the CNN ticker, security has become a pipe dream: you’re only alive because the idiots with guns and an agenda, fortunately, were born elsewhere. Tomorrow is not promised you and yours.

Schools have traditionally been one of the most vulnerable public institutions in the United States. But officials have taken steps in recent years, utilizing existing technology, primarily the Internet and the Google Earth software platform, to reduce that vulnerability. While your odds of being shot are infinitely higher in Mexico (right now), a “lone gunman” is unpredictable. The same could be said for a tornado. A terrorist’s bomb. A fire. An earthquake (don’t laugh; California doesn’t have the market on fault lines).

Beginning in 2004, the Alabama Department of Homeland Security created Virtual Alabama, a convergence of Google Earth and geographic information system (GIS) technology. By the end of the week, Butler County will have been added to the system, allowing first responders with a computer and the Internet access to a wealth of information about each school in the district, including floor plans, utility hubs, evacuation routes, the location of hazardous materials, emergency equipment points, and more.

Lamar Davis, a consultant from Auburn University-Montgomery hired by the Board of Education to implement the program, demonstrated the technology on Monday at W.O. Parmer Elementary. After logging on to the Virtual Alabama website, Davis clicked on a few links to bring up a satellite’s view of W.O.P on the computer screen. Embedded in the map of each school is individual “layers,” said Davis, labeled singularly as rooms, utility points, utility lines, staging areas, chemicals, etc. Clicking on one layer, for example, shows exactly where all fire extinguishers are located in the school (similar to a map’s legend). Another layer identifies all rooms in the school, while another shows the evacuation routes. Photos are also embedded, so that emergency responders can pull up a photo of an electrical panel and know exactly which switches operate what lights in the school.

“Everything is tied in directly with each school’s safety plan,” said Davis.

Virtual Alabama also allows access to the school’s interior and exterior cameras. A first responder arriving on the scene, can click on the layer for “cameras,” note where each is located in the school, and pull up on a laptop an inside view of a hallway or room.

Capt. Anthony Barganier with the Greenville police said tactics for dealing with an aforementioned “lone gunman” have changed considerably. Police departments are now training their officers to act quickly in such a situation, to neutralize the gunman and limit the loss of life.

Someone with a gun and a will to use it, said Barganier, is going to kill. Tools like Virtual Alabama allow officers to make quick decisions, he said.

“It’s a valuable tool all the way around,” said Barganier. “For any type of response.”

Tactical teams, like the GPD’s Special Response squad, can also conduct off-site training by simply pulling a school’s map up on the computer and preparing plans for a specific emergency.

Davis said it takes an estimated two days to completely map the school. Principals at each school provided Davis with safety plans, floor layouts, and any other material needed for the mapping.

Greenville Middle School assistant principal Kent McNaughton said school administrators attended a workshop when the project was in its earliest stages and it was an “eye-opener.”

“There’s just so many things you don’t think of that could happen at your school,” he said.

Given the sensitivity of the information, said Davis, the website is heavily protected. He said passwords and access are controlled by the Alabama Criminal Justice Information Center. Superintendents in each district decide access for law enforcement, fire and emergency personnel.

Davis said state officials have only touched on the capabilities of Virtual Alabama. At the computer on Monday, he pulled up a live map of Interstate 65, a cluster of dots running both north and south. The dots were cell phone signals. A green dot meant the speed limit was being obeyed, a red dot meant it was being exceeded, and a yellow dot meant someone was traveling well below the posted 70 miles per hour.

“A big cluster of red or yellow dots could mean an accident has just occurred,” said Davis.

The Alabama Department of Transportation is also bringing on-line another 2,000 remote cameras, offering live views of the state’s Interstate system.

Big Brother is, most definitely, watching. But, so far, he’s pretty benign.